Now that I've been through the whole cycle, I better understand how decisions I made over a decade ago ended up impacting my team.

When you are first starting a company, you need to set up your ownership structure as represented by a cap table. You and your co-founders will divide up the equity however you see fit, and then you also want to leave a "pool" open for future employees, advisors, etc.

But how big should the pool be and how should you think about employee equity? In the past week alone, I've had multiple first time founders ask me this question. It's not immediately obvious what the right amount is, and it seems like every percentage point you put in the pool is being "taken away" from you.

Your lawyers are likely recommending two things:

- That this should be an options pool, meaning that the space being allocated will be granted in the form of stock options.

- A specific total amount of equity that the pool represents. (Likely 10-20%)

Let's take these each separately, but first a note on working with lawyers in general.

When we started MAZ in 2010, I didn't actually understand what we were doing. We just listened to our (truly amazing) lawyer Pamela. Obviously we figured she's a lawyer who has worked with tons of startups, so she must know better than us! I learned everything I know because of her patience and her dedication to us. That and a ton of Googling and Investopedia articles.

But even with someone as extraordinary as Pamela, I learned, and you should quickly learn, that your lawyer is not the founder or CEO of your business. Only you are. Advice and feedback is always welcome, but your legal team's job is to make sure that you are able to do what you want to do– that it is legal and that it is done properly. But deciding what you want to do really should be up to you.

This is a deep dive on the above points + at the end I'll give you my overall thoughts on how to think about employee equity. (Spoiler alert: be generous.)

How to think about equity: percentage or shares?

If you open Robinhood right now and buy 1 Apple stock, would you know or care what percentage of Apple you own? No, you just care if in the future the price goes up or down.

In startups, founders typically speak in terms of percentage ownership. It's a quick and dirty way to calculate what your take home amount will be upon an exit. If you own 50% and you sell for $50 million, you make $25 million.

In reality, it won't work exactly like that. Different classes of stock might get paid out differently, namely that some investors might have liquidation preferences that ensure that they take back their original investment amount off the top, and then the remainder would be distributed pro rata by percent interest. You also need to deduct closing related costs and other outstanding company expenses.

But, as a founder, percentage is still a useful ballpark way to think about your ownership and what it will mean in the endgame.

For employees, some who might own something like 0.1%, it feels a little less thrilling to hear the percentage. And all the documents they are going to receive are measured in number of shares, not percentages.

Percentages will shift over the lifetime of the company. New investors will come in and dilute existing shareholders, new equity pools will be opened and allocated. The percentage will shift because the total number of outstanding shares in the denominator will shift.

I always tried to make little spreadsheet calculators to share with employees so they could better understand what the numbers on the page meant and to answer any and all questions about equity compensation.

The best and most blunt way I found to explain it is that today you are getting the equivalent value of X ("This is worth $10,000 today"), and if we double the value of the company, that value will be 2X. If we triple, your piece will be 3X. And so on. It puts a dollar amount on what they are receiving, which feels tangible and exciting, and it keeps the focus on growing the company's valuation– which is where you want everyone's head to be at.

What sort of equity to give? All the options suck

So first off, let me be clear that stock options suck in many ways. Why are they so popular? In a sea of bad options (pun totally intended), they still might be the best.

Ideally what you would actually want to do as a founder is just give employees a percentage ownership of the company. If and when you have a liquidation event (sell the company or IPO), everyone gets paid out. Right?

Taxes suck

It turns out that you can't just give someone equity without opening a whole can of worms. If you give an employee stock out of the blue, they will need to pay tax on the value of the stock when they get it, even if they can't sell the stock to cover the tax. Why? Because it's income. You are paying them in stock instead of cash, but it's still income.

If your stock today is valued at $100 (price = valuation / # of shares) and you wanted to give an employee 100 shares– that is $10,000 worth of stock.

The idea is that as the value of the company increases, that stock price will go up. Let's say by the time your company has an exit, the stock price will be $500, and so 100 shares would be worth $50,000. A $40,000 profit! Yay startups!

The problem is that today, when you give those shares out, that employee would owe tax on the $10,000. Let's say at an income tax rate of 30%, that is $3,000 to be paid out of pocket this year. So that still leaves $7,000 you might say? No, because that $10,000 value is illiquid, meaning that the employee can't sell those shares for cash (nor would she want to as the whole idea is to hold that stock and let it grow). So, surprise! You owe $3,000 you don't have.

# of shares = 100

Today's share price = $100

Value of shares = $10,000

Income tax % = 30%

Tax owed today = $3,000

Over the long run if the company really does 5x in value, then it will have been worth it, but you still need to find that cash this tax season.

The only people that can get stock truly for free (or very close) are the founders that are in on day 1. The company is worth zero, and so you are in at the ground level and don't owe any tax because your income tax % of zero is still zero. But everyone from day 2 onward is going to be subject to this tax issue.

RSUs suck

On top of that, if the stock is vesting, meaning that the employee earns it over time, then the tax could be even worse. I like to think of vesting as the company keeping a certain amount of stock with your name on it locked up in a vault, and then you unlock it based on how long you work at the company. Vesting stocks are called Restricted Stock Units (RSUs). Same rules apply as above, except now let's take the same scenario while vesting.

Stock today is valued at $100, and you wanted to give an employee 100 shares vesting 25 each year for 4 years– that is $10,000 worth of stock by today's price, over 4 years.

Let's say it's a year later, end of year 1, and so 25 stocks are "unlocked". By then, the company has grown in value, and the stock price is $200. Awesome!

Except the employee would now owe tax on 25 shares x $200 = $5,000.

Then end of years 2, 3, 4, if the valuation had continued to grow, their stocks would be worth more and more and they'd need to pay more and more tax. Not cool.

# of shares = 100

Today's share price = $100

Value of shares = $10,000

Vesting = 25% end of each year for 4 years

Income tax % = 30%

Year 1

# of shares = 25

Share price = $200

Value of shares = $5,000

Tax owed today = $1,500

Year 2

# of shares = 25

Share price = $300

Value of shares = $7,500

Tax owed today = $2,250

Year 3

# of shares = 25

Share price = $400

Value of shares = $10,000

Tax owed today = $3,000

Year 4

# of shares = 25

Share price = $500

Value of shares = $12,500

Tax owed today = $3,750

Total tax owed over 4 years: $10,500 vs. the $3,000 if you'd gotten it all upfront. 🤮

This is where an 83(b) election comes in which is a cool (I regret saying it already) IRS thing that allows you to pay all the tax upfront at today's value, saving you a lot on tax assuming the company does appreciate in value throughout the vesting period.

Basically you have to inform the IRS within 30 days of your RSU grant that you want to pre-pay for the whole thing, and you get to do that at today's value. So you would pay $3,000 (30% of $10,000) today, even though the stock is vesting.

But it's still cash upfront out of pocket, and what if you decide not to stay for the full vesting period? Or you get fired? Or if the company ends up not doing well a.k.a. the valuation goes down or goes out of business, then of course, the IRS would just give you a refund right? Um, no. Pretty sure they keep your money, and it's lost and gone forever.

Options suck

Enter, stock options! Here you are giving an employee the option to purchase stock later, if they choose, at what will hopefully be a discounted price.

You give the employee the option to purchase stock in the future, at today's price, which is called a strike price. Let's take the same numbers as above.

# of options = 100

Today's price = $100 per share

Value of shares = $10,000

Owed today = $0

Now, let's imagine it's years from now and your startup has a successful exit at 5x today's value, where the share price is $500.

The employee can exercise those options and buy 100 shares for $10,000– and on that same day, those shares are worth $50,000! Fastest investment return ever! (If you don't count all the blood, sweat, and heartache put in over many years before that...)

# of options = 100

Share price = $500 per share

Strike price = $100 per share

Value of shares = $50,000

Exercise price = $10,000

Net proceeds = $40,000

In fact, the company may offer a cashless exercise. In that case the employee doesn't actually need to pay the $10,000, they would just receive the $40,000 ($50k - $10k).

The strike price matters a lot. Employees that get options nice and early when the price is low can really benefit from the growth over time, but employees that come in later / closer to an exit will not see as much gain, and in a downside scenario their options could end up being worthless. That's why I recommend giving more upfront on a longer vesting schedule, rather than multiple grants with shorter vesting periods. (More on that below.)

Tax-wise , that $40k would still be taxed as income, which is not good for the employee. They would have the actual cash in hand to cover it, but that still means a lot of their proceeds are just going to the IRS. The only way to avoid that is if they exercise earlier and hold the actual stock for more than a year to get the benefit of longterm capital gains. But to do that, they would need to pay the exercise price which requires having the cash upfront– and it introduces all the same risks listed above in that if the startup does not succeed, you could lose that money. Ugh.

This is all assuming that the employee stays on the team until the bitter(sweet) end– but what if they leave earlier than that? Or what if you fire them? Let's say that an employee has some vested options and then they are leaving the company. Most options grants have an expiration meaning that within a certain time period after vesting, or more commonly, a certain time period after leaving the company, they need to "use it or lose it". Exercise and get real stock, or forfeit your options.

So let's take our employee example here with 100 shares at a $100 strike price– if they leave the company prior to an exit, then they would need to make the decision to exercise and pay $10,000 out of pocket or to give up their hard-won options. And not only do they need to find that cash, but all the same risks we've been discussing come into play. If the company doesn't end up having a good exit, that money might be lost.

But even if they are confident about future growth, you are basically setting things up so that your best employees with the most options will almost certainly need to forfeit, unless they happen to be independently wealthy. I have actually seen some companies pop up that do lending specifically to fund employee options, but then they are signing up for some serious debt. Options are cost prohibitive for anyone that isn't going to stay on until exit time, which of course most employees will not as that can take 5+ years. (for MAZ, it was 11 years!)

One simple fix for this would be to eliminate or dramatically extend the expiration of options after an employee leaves. Even on a 4 year vesting period, if you have to stay at the company in order to keep your options, it's almost like the vesting period is actually forever.

Right now the standard expiration period is 90 days, meaning that you must exercise or forfeit within 90 days of leaving. What if there was no expiration? If that employee has earned those vesting options fair and square over the duration of their vesting period, why wouldn't you let them keep them? Why force them to exercise or more likely, forfeit? Seems unfair. Your lawyer will likely raise their eyebrows when you suggest this, because it's irregular. But remember, it's your company. If it's not illegal or unethical, I say it's fair game. I wish we had known to do this earlier on.

Other alternatives suck but maybe are cool

What else can you do instead of options or RSUs? One possible alternative is phantom stock. Besides clearly having the best name, it avoids some of the pitfalls of RSUs and options but of course has other drawbacks of its own.

Phantom stock is basically a contractual agreement to pay a given employee a certain amount if certain conditions are met, simulating what would have happened if they had owned stock, but without the rigamarole of actually giving out stock or options.

This could also be called a change of control bonus or an employee carve-out. It's a bonus that is only paid out when a certain predefined set of circumstances happen.

For instance, you might say that if there is a liquidation event (defined as XYZ), then the employee will receive 1% of the total proceeds. You could also make it a fixed amount, or any other arrangement of your choosing.

So let's say, you create a phantom stock plan where an employee is going to receive whatever the equivalent value of 100 shares is at the time of an exit event.

# of phantom shares = 100

Share price at sale = $500 price

Value of phantom shares = $50,000

In this example, the employee gets $50k, but there is no exercise price. They just get the full cash amount. Sweet!

However this full amount is again taxed as income, not longterm capital gains, similar to options that are exercised at the time of a transaction. But at least here they are getting the full value, not the net proceeds after exercising, because there is no strike price! It's just a pure cash bonus.

One other thing to consider with phantom stock is where in the pecking order these types of distributions sit. If there are preferred investors that get paid out before common stockholders, for instance, where do the funds for phantom stock payouts come from? Off the very top or off the amount left after the preferred get paid?

If an employee is not going to exercise their options early and hold their stock for longer than a year, phantom stock seems like it might be a better route. On the other hand, some people like to know that they really own a piece of the company, and the concept of "fake" stock might be a turn-off.

One last thing is that unlike real stocks, you can create a phantom plan at any time, even if your existing equity pool has already been used up. You would need all the necessary approvals from your board, investors, etc. (which is the case for everything we're discussing), but you can create these types of bonus structures on the fly to ensure that underrepresented employees get a piece of the action as part of your planning process pre-exit.

How big should your pool be?

Now on to the second point of how much to allocate for employee equity. There is no right answer per se, but I think the average is going to typically be 15-20%.

If you are planning on raising money, investors will almost always ask for a pool in this range, and they will ask that it be re-upped before they invest. That means if you had a 15% pool but have already given out 5% so only 10% is still open, a new investor might request that you open it back up to the full 15%, diluting all the existing shareholders, before they put in new money. In other words, they want the pool to be bigger, but they don't want to be diluted.

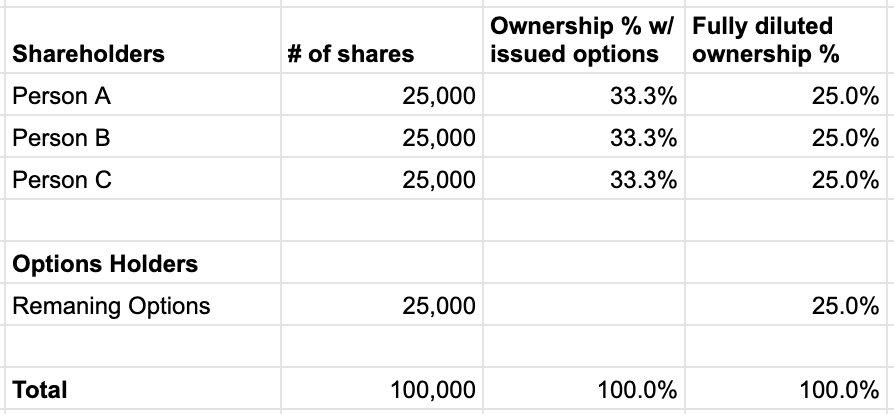

Another thing to keep in mind that an options pool is just a maximum amount that can be granted. If you have a 20% pool, and you grant none of it, then it is effectively 0%. Or if you grant some, but those employees never exercise, then it is still effectively 0%. This is why in a cap table you will see two columns calculating percentage interest– one based on issued options and one showing fully diluted ownership. The former calculates each shareholder's % assuming that issued options are eventually exercised. The latter shows what the %s would be if the entire pool was issued and exercised.

Imagine a scenario where there are 3 co-founders + a 25% options pool, but where no options have been issued yet. Right now, each co-founder still owns 33.3% of the company.

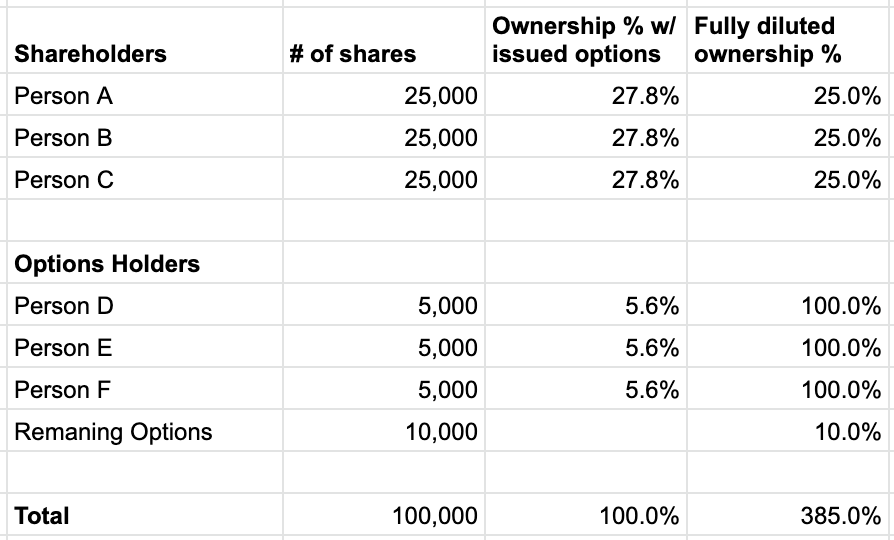

Now let's say that we give 5,000 options each to Persons D, E, and F. Note the differences in the two ownership columns.

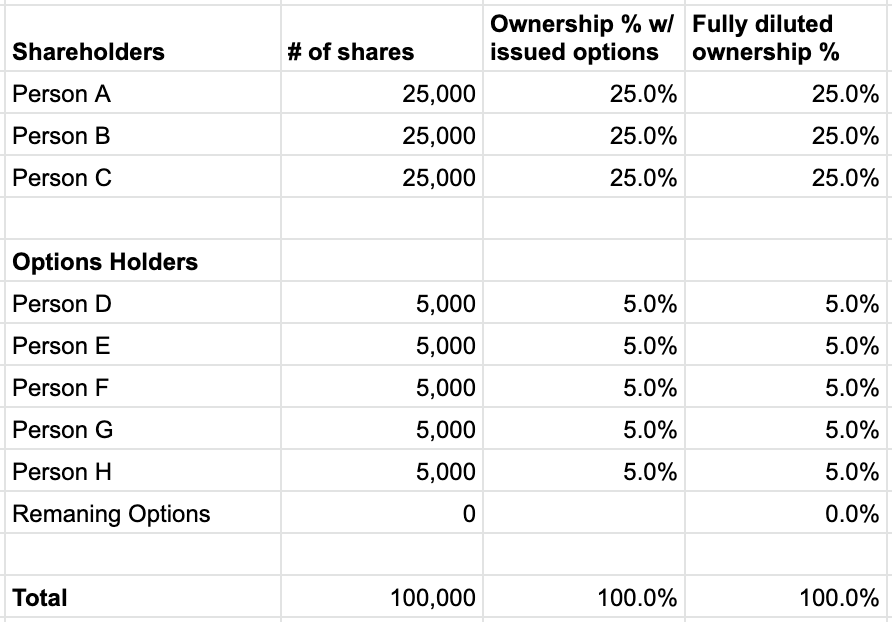

And if we grant all the options in the pool with none remaining, then the two columns would appear identical.

Keep in mind, even then, it only plays out this way if everyone with an options grant ends up exercising. And almost certainly, some won't.

When that happens, you can either leave those forfeited options open (distributed back to the rest of the cap table), or you can reissue some or all of it to others.

How much equity should you give to employees?

As for allocations– there is no one-size-fits-all answer. What I can offer are some frameworks and general thoughts on how to approach it.

Early in a startup's life, equity is cheaper than cash. At some point, it flips. Not only that, but you won't actually have any cash! At least, not enough of it.

To attract good talent, you won't be able to compete on salary, benefits, cachet, a nice office, or basically... anything. That is, except for equity. Equity that today is not worth much, but in the future could be worth a whole lot more than whatever you'll get from Meta or Google! Don't be another cog in some corporate machine, come build the future with us and participate and infinite upside! That's what you are selling.

Also it should be noted, that the real incentive for early employees is going to be your company's vision. Equity is how you make the compensation package competitive, yes, but it's not actually how you're going to attract great people. That is going to be about you, your mission, and your team.

In practice, there are going to be a few key, senior and/or early hires that you are going to need to pony up for. These folks know and understand the value of startup equity (which more junior employees might not– more on that in a second), and you should want them to have a significant stake, because without their contributions, you will be much less likely to succeed. If that is the case, if they can help you win big, they should win big too! And if that's not the case, then why are you hiring them?!

For other players on your team, it might not be so make or break, but you will still want them to feel aligned with the longterm vision. Equity that vests over time is a great retention tool.

Should you give equity to everyone? As the company grows, and you can be competitive on salary and other benefits, that will be enough to recruit great talent, without an equity component. But even small amounts to make everyone feel like an owner (by actually being an owner)– that's pretty powerful.

Like with other types of compensation, the squeaky wheels often get the oil. If you have a savvy employee or prospective employee that knows to fight for more equity, and they are an asset, you will be more likely to give them more than someone that doesn't know to ask. Over time, I realized this and started to advocate more on behalf of people that maybe didn't know how to advocate for themselves.

As a general rule, in negotiations about equity, I like to present cash and equity as two levels that can be pulled, but not both at the same time. More cash means less equity. More equity means less cash. That conversation helps you understand the priorities of the employee, their appetite for risk, and it gives them some autonomy in deciding how they want to structure their compensation.

Regarding vesting schedules– standard these days seems to be something along these lines:

4 year vesting <– total time until 100% is vested

1 year cliff <– meaning nothing until after 1 year

25% after 1 year <– 1/4 of the total amount vests

25% each subsequent year* <– 1/4 unlocked at the end of year 2, 3, 4

*or this could be 1/12 every quarter or 1/36 every month

If an employee stays on for the full 4 years, you might consider giving them more to incentivize them to stay longer...

Should you re-up people over time, including yourself?

Yes. For lots of reasons, but yes. This is good for ongoing retention. It's good for morale. It helps fight dilution as you raise more outside capital. Your investors will likely get pro rata rights, meaning that they can re-up their stake to maintain their previous percentage interest. You and your team should get the equivalent.

I never asked for it for myself, because I wanted to make sure whatever we had to give went to the team. But in retrospect, I should have. Not because I am greedy, but because you should apply the same logic to yourself as an employee that you do to other employees (in my case, I was employed as CEO working for a salary for many years long after my equity vested).

Ideally, your board will fight for this on your behalf, just like you should fight for your team. But like I mentioned above, those that advocate for themselves usually get more, and that includes yourself.

That being said, with stock options, an even better approach would be to give more upfront over a longer vesting period. Why? Because if you give an employee a new grant in 4 years, the strike price will be at that new valuation, which is worse for the employee. But if you give them 2x the options over an 8 year period today (same total amount over same total time), all of it could get the benefit of today's strike price. Sometimes this is not possible because the pool isn't big enough upfront to give everyone 8-10 years of vesting, and you need to take a hard look at acceleration clauses (do you want someone to get 8 years of stock if the company sells after they've only been there 1 year?)– but if things go well, that strike price is going to shoot up, making all subsequent options worth less and less.

How I felt about all this when we finally sold and the money hit the bank

The most gratifying thing about selling was knowing that the people who deserved to be making money, did. Building a startup is a team sport, and I went to great lengths to ensure that there were many winners, not just us as the founders.

There was zero part of me wishing I'd hoarded more for myself. If anything, I wished for the opposite. I wanted to go back in time and somehow reward every one of the hundreds of people that had contributed over the years. Every early employee. Every random intern. New hires that had only started weeks before we sold.

Surround yourself with amazing people, and share the love!!! (Love = equity in this case)